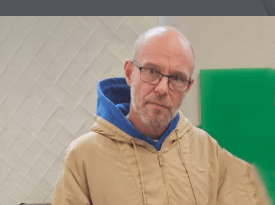

Following the unexpected news of his death, Pono’s age, which was searched as Pono wiek, started to circulate with remarkable speed. The questions spread over social media like a swarm of bees responding to a disturbed hive. These discussions have taken on greater significance in recent days as fans reread the plot of his 49-year career, following the artistic trajectories he sculpted with a discipline that remained remarkably apparent even amid the most volatile periods of Polish hip-hop. His career, which was molded by perseverance and bold decisions, feels incredibly successful in illustrating how a single artist can make a complex impression on a whole generation.

He entered the music industry during the early years of Poland’s rap movement, when its aural identity felt fluid yet promising. He was born in Warsaw in 1976. The early setting was remarkably flexible in its potential but drastically limited in structure, enabling up-and-coming artists to experiment with themes and rhythms without strict constraints. He started recording with TPWC in 1996, which was the start of his career ascent. He co-founded ZIP Skň a year later, which turned out to be a particularly creative decision as the organization assisted in establishing a cultural shift that resonated throughout districts and youth circles.

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Rafał Artur Poniedzielski (Pono) |

| Birth | October 6, 1976 – Warsaw, Poland |

| Death | November 6, 2025 – Warsaw, Poland |

| Age | 49 |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Profession | Rapper, Music Producer, Activist, Entrepreneur |

| Notable Groups | TPWC, ZIP Skład, Zipera |

| Active Since | 1996 |

| Organizations | Hey Przygodo Foundation, 3Label |

| Collaborators | DJ 600V, Vienio, WWO, Hemp Gru, Pelson, Fu |

| Reference |

His partnerships provide a road map of his creative development, emphasizing the increasing convergence of various Polish rap sounds. He developed a style that was noticeably enhanced with each project while collaborating with DJ 600V, DJ B, Włodi, Vienio, Fu, Hemp Gru, Ascetoholix, and the White House collective. He maintained an incredibly dependable artistic identity while broadening his musical language through clever alliances. By simplifying processes and releasing creative energy, these partnerships acted as catalysts, encouraging him to experiment with new cadences, tempos, and production techniques.

Throughout the 2000s, Pono moved between several roles—producer, mentor, and performer—with a fluidity that felt far quicker than many of his peers. He investigated stories influenced by personal struggles, urban grime, and the shifting cadence of Polish streets while performing with Zipera. He pursued solitary work during group breaks, showing how his independence was remarkably resilient even when he took a break from group initiatives. Because of his versatility, he was able to stay relevant throughout changing musical eras, displaying a talent that fans praised as both restless and grounded.

His influence extended beyond music to include activism and business. He and windsurfer Zofia Klepacka co-founded the Hey Przygodo Foundation in 2006. The foundation’s goal of helping talented kids who are struggling financially was especially helpful for young artists looking for reliable guidance, equipment, and mentorship. This program proved to be quite effective in spotting potential early on and providing structured help that many families could not afford in the context of long-term social mobility. The foundation’s work continues to be a very obvious example of how artists may use publicity to influence change.

His business acumen was further enhanced in 2009 when he and Michał Makowski co-founded the 3Label record label. For up-and-coming performers who frequently lacked institutional support, the label provided an unexpectedly inexpensive entry point by using independent production techniques. Securing sponsorship is still the largest obstacle for up-and-coming rappers, but his actions greatly lessened it. The label’s strategy, which was based on cooperation and resource sharing, was similar to global systems in which musicians like Stormzy or Jay-Z created platforms that benefited entire communities rather than just their own careers.

Remote labor changed artistic practices in many professions during the pandemic, but Pono adapted with the same tenacity that saw him through previous decades. He continued to be quite busy, performing, recording, and interacting with fans, keeping up a very dependable presence during a period when many musicians felt lost. He was in noticeably better form during his concerts just before he passed away, including one in which he performed with Molesta. He was energized, focused, and emotionally present. His enthusiasm had not diminished, as seen by the events he had planned, including the 120rapfest on November 14.

He joked that he felt “more lubricated” in a video he shared during a physiotherapy visit two days before he passed away. Nothing alarming was implied by the tone, which was informal, comfortable, and even lighthearted. Later, the physiotherapist sent him a touching email in which she thanked him for the session and expressed her appreciation for getting to know him better. Those last clips, which showed commonplace events captured right before the unimaginable, proved surprisingly moving. Fans found it difficult to reconcile the vividness of those films with the finality of his absence after learning that he had passed away at the age of 49.

With a raw tenderness that touched multitudes, Wojtek Soków took on the difficult responsibility of announcing Pono’s passing: “My friend died today, the man I started recording rap with, a legend and individual.” incredibly gifted and even more obstinate. His eulogy was remarkably affectionate, demonstrating the close connection between their lives from the beginning of their careers. In a matter of minutes, the post turned into a hub for journalists, artists, and admirers. The portrait continued to be painted with messages from Peja, Fu, Liroy, Pelson, and innumerable others.

Tributes have grown dramatically on all platforms since the start of public mourning, demonstrating how much Polish culture depends on the musicians who created its soundtracks. Cultural institutions have begun to reexamine how early hip-hop impacted social narratives in the 1990s and 2000s, changing conventional views of teenage identity in the field of education. His writing, which frequently alludes to common goals and hardships, is still relevant today.

Rap storytelling traditions have been increasingly significant over the last ten years, reflecting consumers’ desire for authenticity in the face of digital cacophony. Pono’s lyrics, which are frequently based on genuine conflicts and individual resiliency, feel especially avant-garde in their fusion of philosophy and rawness. In times of change, his robust yet reflective tone provided listeners with a sense of stability. He was characterized by many as emotionally resilient, able to handle disagreements without letting them destroy his sense of direction.

Cultural observers anticipate that conversations about longevity, mental health, and creative burnout will become more intense in the upcoming years. The discourse is even more necessary because his death, which happened during a period of professional stability, brought to light problems that are startlingly comparable to those faced by artists worldwide. A story of a guy who gave freely, expected excellence, and refused to compromise his integrity emerges when fans examine interviews, lyrics, and backstage film.