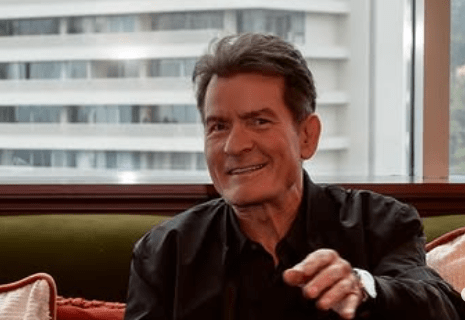

The amount of time spent talking about Charlie Sheen’s height—officially 178 cm, or about 5 feet 10 inches—is a subtle irony. It’s a detail often repeated with robotic precision on fan sites and celebrity profiles, as if that number offers some key to understanding his odd fascination. But Sheen’s physical size has always played second fiddle to something less measurable: presence.

Born in New York City and raised under the California sun, Charlie—then Carlos Irwin Estévez—was part of a family already steeped in performing. His father, Martin Sheen, wasn’t simply famous—he was respected. That shadow might be intimidating for any child. For Charlie, it seemed like challenge accepted.

| Full Name | Carlos Irwin Estévez (Charlie Sheen) |

|---|---|

| Height | 178 cm (5 ft 10 in) |

| Date of Birth | September 3, 1965 |

| Known For | Platoon, Wall Street, Two and a Half Men |

| Parents | Martin Sheen, Janet Estévez |

| Children | Sam, Cassandra, Lola, Bob, Max |

| Highest Salary | $1.25 million per episode (Two and a Half Men) |

| Health Disclosure | HIV-positive since 2011, publicly confirmed in 2015 |

| External Reference |

He broke through, notably, with Platoon in 1986. That picture didn’t just win awards—it startled viewers into quiet. Sheen’s portrayal felt grounded and haunted, as if he’d witnessed more than he let on. In Wall Street the following year, he switched combat boots for business suits and gave a Gordon Gekko–adjacent portrayal that echoed the decade’s pessimism. Both professions required more than talent—they demanded weight. And Sheen, not very tall by film standards, never looked dwarfed by the screen.

The pivot came soon. From the 1990s onward, his choices got cheeky. Hot Shots! and Major League played off his former seriousness by spinning it on its head. Watching him fake puke or blunder through air combat as Topper Harley was particularly humorous because of who he had been before—a leading guy choosing not to take himself too seriously. It was a considerably enhanced form of comedic range, unexpected yet indisputably effective.

By the time Two and a Half Men premiered in 2003, Sheen had carved out a peculiar space: a man whose off-screen volatility only added edge to his on-screen image. Not only did the sitcom succeed, but it flourished. His character, Charlie Harper, wasn’t a stretch, but the lines between performance and daily life got increasingly muddled. He provided the dry humor, the timing, the shrugging arrogance. And it paid off—literally. Sheen earned an incredible $1.25 million each episode at the height of its popularity, making him the highest-paid actor on American television.

He converted volatility into market value by taking advantage of his own contradictions. I remember watching him exchange lines with Jon Cryer and thinking—not about jokes—but about tempo. His timing wasn’t just sharp; it was instinctual, like someone who understood stillness just as well as punchlines.

But stardom bends under its own weight. Sheen was sacked from Two and a Half Men in 2011 as a result of a string of public altercations, drug admissions, and remarks that sounded like performance art. “Tiger blood” became a meme. So did “Adonis DNA.” Through the mist, one could see a guy torn between show and reality, fostering a kind of notoriety that was both addicting and destructive.

Later the same year, Sheen returned with Anger Management. The program provided stability—a chance to perform without collapsing—even though it never managed to recreate his former magic. It went for 100 episodes, a record that was surprisingly astounding for someone widely written off at the time.

Then followed the most vulnerable admission of all. Sheen revealed in 2015 that he had been HIV positive since 2011. The announcement was calm, even calculated. There was no great display, no deflection. Just the facts. His transparency produced a rare flood of popular empathy, piercing through years of tabloid caricature.

That moment didn’t undo the damage—too much had already accumulated—but it humanized him. It added weight to the gentler chapters of his life, the ones without TV crews or judicial drama. Since then, Sheen has taken a step back. less news stories. Less noise. A man, perhaps, learning how to exist without the pandemonium.

At 178 cm, Sheen stays somewhat below normal height for a German guy, but over for an American. It’s an arbitrary number, yet weirdly overanalyzed. More beneficial is this: he’s tall enough to fill a frame, but never so towering as to be unrelatable. He is in the middle of the extremes. Not the tallest, not the shortest. Not the hero, not the villain. Charlie alone.

Sheen’s height serves as a reminder of how ridiculous our metrics may be in the setting of celebrity measurement, when shoe sizes and net worths are traded like money. For a man who once strolled across prime-time television with a tumbler in hand and a sneer no one could mimic, the tape measure feels like a lousy substitute for influence.

He created a very adaptable identity by strategic decisions—and occasionally strategic chaos. He moved between film and television with casual ease, often redefining what fans expected from him. Even at his lowest, there was something notably captivating, something you couldn’t quite turn away from.

For all the parts, all the interviews, all the scandals, Charlie Sheen has never begged to be understood. Perhaps that’s why we keep trying.