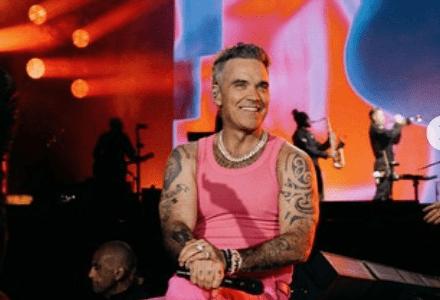

Robbie Williams doesn’t present his diagnoses in a tidy manner for the general public or wear them like medals. Slowly and even awkwardly, he shares them with a startling honesty that speaks more than any polished vulnerability could. He has spent decades attempting to strike a balance between an inward experience that frequently feels relentlessly loud and a job based on spectacle.

Although he originally discussed ADHD in 2006, he hasn’t been revealing further details until recently. Anxiety, melancholy, body dysmorphia, and now what he refers to as “internal Tourette’s”—an unending wave of intrusive ideas that seldom show up externally but continually swirl inside—are among the diagnoses that have piled up like used suitcases. He claims that these ideas are unaffected by whether he is standing by himself in a dressing room or performing in front of 50,000 fans.

| Name | Robbie Williams |

|---|---|

| Birth Year | 1974 |

| Nationality | British |

| Notable Career | Member of Take That, solo pop artist |

| Known Health Issues | ADHD, body dysmorphic disorder, depression, anxiety, substance abuse, Tourette-like symptoms |

| Family | Married to Ayda Field; four children |

| Reference Link |

Usually, Tourette syndrome manifests as physical or vocal tics. However, Robbie’s description aligns with the wider spectrum, which is dominated by mental tics. Thoughts flood in, relentless and unwanted. He feels more cramped than others who might hear cheers or feel the atmosphere of a stadium. In an interview with a podcast, he acknowledged, “I can’t take it in.” For someone whose livelihood depends on connection, that kind of disconnection—where achievement becomes a blur—feels especially cruel.

Then there is the mirror, which has never provided him with a true reflection. He has had body dysmorphic disorder for years, which causes him to have a distorted view of his physical appearance. What he saw didn’t match reality, even when he was at his leanest or fittest. He has occasionally taken detrimental turns due to his desire to “fix” that discord. For example, he just contracted scurvy, a disease that many people thought was relegated to the past, as a result of his experiments with appetite suppressants. In his quest for thinness, he had essentially starved his body of vital nutrients.

He started using Ozempic-like weight-loss injections more recently. Although the medications reduced hunger, they also raised new issues. He freely expressed concerns that they would impair his vision. He seemed to be especially conscious of this pattern: trying to resolve one problem only to uncover another. These are not isolated medical facts; rather, they paint a picture of a person constantly attempting to adjust a body and mind that are uncooperative.

Naturally, addiction has always played a role in Robbie’s story. He started using drugs and alcohol in the 1990s, with periods of recovery and hospital stays interspersed. He doesn’t treat sobriety as a destination, nor does he romanticize that phase. Rather, he presents it as a continuous process that needs to coexist with anything else that his mind can think of.

His openness about touring is what many people find most impressive. He acknowledges that it frightens him. Even with a thirty-year career, every tour is filled with dread rather than excitement. It’s natural to think that the stage must suddenly seem cozy. Every performance, however, might feel to Robbie like walking on a tightrope and not knowing if the balance would stay. “People assume that when a tour is approaching, I should be ecstatic. I’m actually afraid,” he once remarked.

His public persona frequently contradicts that dread. He is loud, nimble, and engaging on stage. He is reflective and somewhat uncertain offstage. Both viewers and, apparently, he find that contrast confusing.

This disparity is attempted to be charted in the 2024 biopic Better Man. It doesn’t skip the dark points; instead, it starts with his early years and tracks his ascent through Take That and into solo superstardom. His battles with drugs, mental illness, and the ongoing conflict between celebrity and well-being are all featured in the movie. It is a realism arc rather than a redemption arc.

His family now seems to be a major source of his stability. Since 2010, he and Ayda Field have been wed, and together they have four kids. He frequently talks about her in interviews with adoration and affection. She soothes the jagged edges of self-doubt, gives him encouragement, and reminds him of how far he has come. He claims that being a parent has been a “beautiful journey”—a statement that has great meaning for someone as publicly cynical as Robbie.

Parenting appears to provide stability and a sense of purpose unrelated to praise or financial achievement. Grounding is what it is. It tethers him when anxiety could otherwise take over, but it’s not a cure. He takes great effort to portray his kids as the most honest aspect of his life rather than as his saviors.

Additionally, he seems to have become more picky about what matters as he’s gotten older. Once a constant pressure, public opinion today appears to be less significant. He is still performing, recording, and interacting, but he has set new boundaries. He is actively attempting to explain what a sustainable job entails when one’s own thinking can be a powerful enemy.

This is not a triumphant tale in the conventional sense. It’s about overcoming a mentality that doesn’t always comply so that you can still show up, choose to produce, and dare to interact with others off stage. Robbie Williams allows others to talk more freely by embracing the complexity of his ailment rather than avoiding it.

The hope in this situation stems from the clarity more than the lack of disease. He is aware of the situation. He gives it a name. He gives it away. By doing this, he eliminates guilt from circumstances that all too frequently depend on quiet.