Something that hardly feels medical can be the first step. a wrist that is difficult to twist properly. Button-fumbling fingers. It’s just a weird disconnect between intention and execution, not pain. Everyday tasks become strangely difficult, such as attempting to use scissors with one hand. The symptoms of motor neurone disease are subtle. It waits. Then it starts to alter everything, bit by bit.

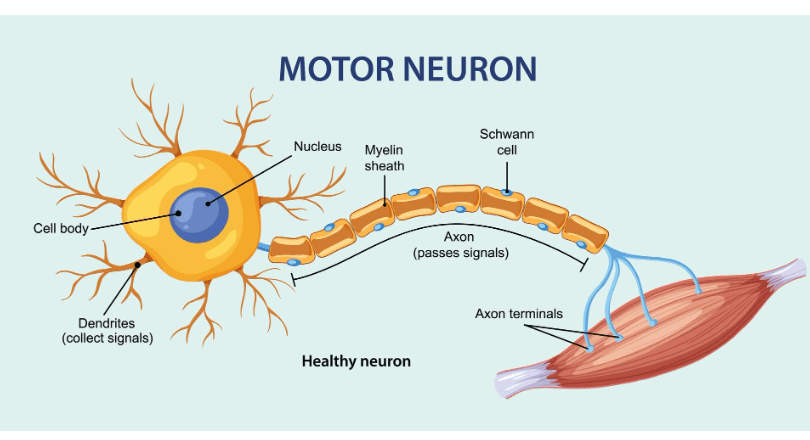

It impacts motor neurons, which are essential links between our muscles and brains. The muscles they control become useless when those cells start to malfunction. Arms cease to raise. Legs pause. It becomes difficult to swallow. Even breathing eventually turns into a controlled, conscious action.

Motor Neurone Disease – Key Facts Table

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Condition | A progressive neurodegenerative disease affecting nerves controlling voluntary muscle movement |

| Typical Onset Age | Commonly diagnosed after age 50 |

| Early Symptoms | Weak grip, foot drop, frequent tripping, muscle cramps, twitching |

| Common Subtypes | ALS, PBP, PMA, PLS – each affects different muscle groups initially |

| Diagnosis Methods | Blood work, nerve conduction tests, MRI scans, neurological assessments |

| Treatment Options | Riluzole, physiotherapy, speech therapy, ventilation support, mobility aids |

| Progression | Gradual muscle wasting; leads to breathing, swallowing, and speech difficulties |

| Support Resources |

ALS, the most prevalent kind, is scriptless. Some patients initially experience hand weakness. Some people trip more frequently. Long before anything else, people with progressive bulbar palsy may slur their words. Because of its unpredictability, the illness resembles a shapeshifter in that it is constantly evolving and rarely predictable.

Many people experience delayed diagnosis due to complexity rather than carelessness. MND mimics. It poses as vitamin deficiency, foot drop, or carpal tunnel syndrome. Despite their best efforts, a general practitioner may require time and a team of experts to gain clarity. Even in those cases, the confirmation frequently comes with a heavy silence rather than relief.

Every other possibility is systematically ruled out. The results of blood tests are normal. Brain scans don’t show much. However, studies of nerve conduction start to reveal the truth. And when it becomes apparent, the emphasis changes from curing to precisely managing each symptom.

Surprisingly, most people’s minds stay remarkably sharp even as their muscles deteriorate. Thoughts continue to develop. Recollections remain clear. However, the capacity to articulate them diminishes. Perhaps the most emotionally taxing aspect of the illness is the dissonance between the external deterioration and the inner vitality.

A medication called riluzole, which can slightly slow the progression of the disease, is given to some patients. Physiotherapists teach exercises to help people maintain function for as long as possible. Once voices start to fade, speech therapists suggest tools that can fill the gap, which are frequently surprisingly inexpensive.

Not all forms of support are clinical. I once heard from a speech therapist that she prefers creating picture boards and modifying iPads to doing traditional therapy. She clarified that immediacy, not elegance, is what people most need.

The physical environment must change as movement decreases. restroom grab bars. beds that can be adjusted. vehicles that have been altered. Because swallowing becomes difficult, even eating can become difficult. Despite being emotionally taxing, tube feeding is a remarkably effective way to maintain energy and weight.

Emotionally, MND asks a lot. People face a narrowing set of options—and yet, within that narrowing, they find ways to stay expansive. They take up eye-tracking software to write letters. They schedule voice banking early on, preserving messages for children or grandchildren in the exact tone they’d recognize. These decisions are deeply personal. And always forward-looking.

For about 1 in 10 patients, genetics plays a role. A mutated gene, passed from a parent, creates a family thread that can feel unbreakable. But the vast majority of cases appear without warning, without history, without any clear trigger. This randomness is unsettling, but it’s also democratic in a way: MND does not discriminate by background, status, or lifestyle.

The lead neurologist at a clinic I visited in 2023 made the subtle but impactful statement, “We treat the patient’s time as more valuable than our own.” Each appointment was meticulously planned. There are no delays. No needless waiting lists. It served as a reminder that logistics are where respect for chronic illness starts. That line made me pause, I recall. Beyond medicine, it seemed like a philosophy worth adopting.

Despite the seriousness of the illness, many people manage to stay connected and feel seen in remarkably effective ways. One woman I spoke with organized an art show with pieces created with just one hand using what strength she still had left. Money for accessible tools was raised at the exhibition, which took place in a small community center. More significantly, though, it increased awareness.

This spirit—honest, resilient, and incredibly inventive—is what keeps influencing how care teams handle MND. Patients receive much more than maintenance when assistive technology is incorporated early on and interdisciplinary collaboration is fostered. They are provided with significant continuity.

Our knowledge of the disease’s molecular mechanics has significantly improved over the last ten years. Trials investigating stem-cell applications and gene silencing treatments have progressed from concept to clinical testing. Although a cure is still a ways off, we are no longer in the dark. Every new development, no matter how minor, contributes to an increasing amount of hope.

MND became more well-known in the culture thanks to initiatives like the Ice Bucket Challenge. However, the actual work has always been more personal and less widely shared: spouses going to mobility training, families learning how to use ventilators, and kids watching a parent’s voice turn into text.

The Motor Neurone Disease Association continues to be a very creative informational, advocacy, and experience-sharing organization. Their helplines, regional groups, and digital toolkits cover a gap that formal healthcare occasionally overlooks. They are particularly useful as a connective tissue in rural areas.

Many patients experience emotional instability in the early stages of the illness, not out of fear but rather from the unfamiliarity of losing strength without losing identity. Talking therapies have been very successful in helping people reframe their experiences, particularly cognitive behavioral approaches.

The patient’s circle expands along with their care needs. Speech pathologists, social workers, occupational therapists, and ventilator specialists. Together, they create a net to walk with someone as they acclimate to new terrain, not to catch them falling.